Quantum-computing hardware development: From dream to reality—AOKI TAKAO×FURUTA AYA

Project Manager (PM) Aoki Takao leads Large-scale quantum hardware based on nanofiber cavity QED, a Moonshot Goal 6 project pursuing a totally new approach to quantum computing.

It was in 2020, with his laboratory shut down by the COVID-19 pandemic, that PM Aoki first began thinking seriously about an idea that, till then, had been confined to a corner of his mind: preparing to launch a company. That company—a quantum-computing hardware startup, the likes of which had never been seen in Japan—was founded in 2022 and is now sprinting through its growth phase.

But why did PM Aoki found a startup, and what does he hope to achieve? And what has been the key to the company's success in raising capital? We take a deep dive into these questions with Furuta Aya, a veteran reporter and editor for newspapers and science magazines with decades of experience reporting on the world of scientific research—and a thorough understanding of quantum computation, including overseas developments.

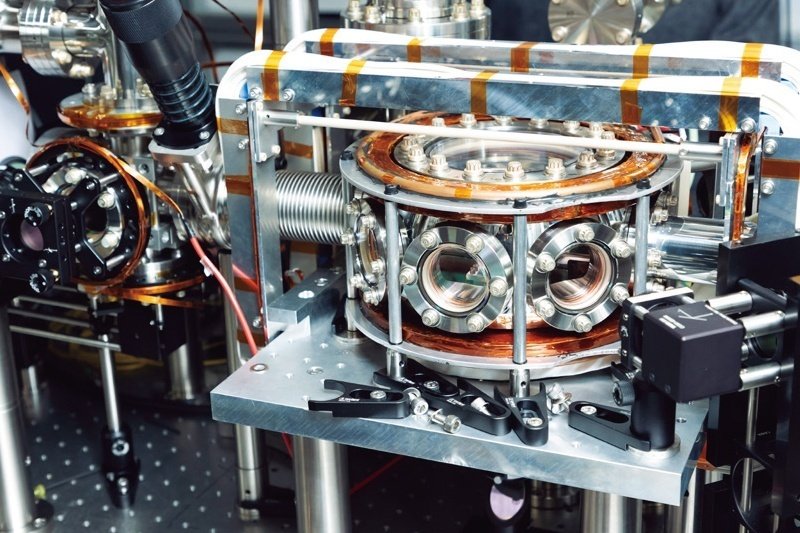

《PM Aoki’s research project on cavity-QED-based quantum computers》

The missing link in Japanese quantum-computer research

Furuta: Professor Aoki, I understand you've recently launched a quantum-computing startup named Nanofiber Quantum Technologies (NanoQT). What are your goals for this company?

Aoki: In 2014, I built what I called a “nanofiber cavity-QED system”, which used photons to mediate efficient interactions between atoms. After thinking a bit about how best to exploit the unique characteristics of this system, I came to believe very strongly that it offered an overwhelming advantage, compared to other known approaches, in its ability to realize distributed quantum computing by interconnecting multiple cavities via optical communication channels. So then, as I was pondering optimal strategies for advancing this idea, it occurred to me that many of my fellow researchers in the U.S. and Europe—people who presented their research in the same sessions I attended at international conferences—tended to launch startups based on the fruits of their research at early stages, after which the research proceeded at turbocharged speed.

Furuta: That’s really true. I’ve noticed that quantum-computing architectures based on solid-state devices using materials such as superconductors or semiconductors are being developed primarily by large tech companies with experience in computer research, like IBM, Google, and Intel—but that approaches using natural qubits like atoms, ions, and light, are largely driven by university-based startups, mostly in the U.S. and Europe.

Aoki: That’s precisely why I started thinking about launching a startup. Quantum computers are still mostly confined to the realm of basic research, with not much visibility for practical applications on the horizon. Nonetheless, societal expectations are huge, and a promising startup can raise surprising amounts of capital from private investors. In the U.S. and elsewhere, startups raising capital in this way have been able to advance their R&D goals with speeds that leave even first-class universities in the dust.

For example, IonQ, which uses the ion-trap approach, was founded by Chris Monroe and others at the University of Maryland. At that time they could only build systems with a few qubits, and I remember thinking “Wow, those guys are impressive!” But after that their research proceeded unbelievably quickly, and now they’re running quantum-computing machines with several tens of qubits. More recently, QuEra Computing, a startup founded by Mikhail Lukin at Harvard, Vladan Vuletic at MIT, and others to develop hardware based on cold atoms, has been generating very noteworthy results.

However, at that time there was no startup in Japan whose mission was to get right in the middle of things and start developing quantum-computer hardware, and that struck me as a very precarious situation. One reason for starting NanoQT was to build that sort of R&D organization in Japan.

Furuta: I see. I remember that there were some information and communication technology companies in Japan, like NEC and NTT, which were actively working on quantum computation research in the 1990s and the 2000. I sometimes heard from researchers from abroad that it was enviable that industry invested in such far-sighted research. However, over the following 10 years the situation changed, and for a time there were almost no companies in Japan that were engaged in hardware development. However, more recently, we’ve started to see an uptick in that direction. Am I right in saying that NanoQT was the first Japanese startup focusing on quantum-computing hardware development?

Aoki: That's correct. There are a few startups developing quantum-computing software, but I believe we’re still the only startup doing hardware R&D.

Creating a new career path for researchers

Aoki: Another reason I wanted to launch a startup was to create an environment in which young researchers in Japan could devote 100% of their energy to pursuing their research—with adequate resources, and without having to worry about career and lifestyle stability.

In the U.S., for example, the most talented PhD students join startups after they graduate. After all, the compensation and benefits are generous, and all of that copious funding from investors allows researchers to devote full attention to achieving their stated goals—and generating huge breakthroughs. As a career path, landing a job at a quantum-information-technology startup is considered just as desirable as becoming a tenured professor at a good university—if not even more desirable.

In Japan, by contrast, even after putting in all the blood, sweat, and tears to complete a PhD, most students can find no positions other than postdoctoral research appointments with single-year contracts. These positions are not well-paid, and they leave people feeling perpetually anxious about what they're going to do next year. And yet somehow, under those suboptimal conditions, we ask people to push forth their research fueled purely by passion alone, generating results in the hope of landing an extremely competitive tenured position. If Japan offered career paths similar to the startup trajectories available in the U.S., talented young researchers would be able to devote full attention to their research.

Furuta: Many people have pointed out the very harsh environment for young researchers in Japan, and, indeed, the number of students starting PhD courses has been dropping due to anxiety over future career and lifestyle trajectories. With graduate-school enrollments increasing overseas, this would lead to a decline in Japan’s capabilities in science and technology. So what you’re saying makes perfect sense to me. But in Japan is it really possible, even for university-based startups, to raise enough capital to hire talented graduates and provide attractive pay?

Aoki: There’s no question that the pool of investors, and the amounts they invest, are orders of magnitude smaller in Japan than in the U.S. This is why we relocated NanoQT headquarters to the U.S. in the summer of 2023. Our goal is to get to a point where we can raise capital from investors on a global scale, and as of September 2023 we had raised 8.5 million dollars (around 1.25 billion yen at exchange rates of that time).

Furuta: When was NanoQT founded?

Aoki: In April 2022.

Furuta: So you’re still relatively new.

Aoki: We reached the original conclusion—that our plan for realizing quantum computers based on nanofiber cavity-QED was a go—in early 2019. Then we spent some time thinking about how to advance our research goals, and we finally decided to start the company in March 2020. However, it took around 2 more years before NanoQT was actually launched. What we were doing during that interval was looking for a CEO. Quantum technology definitely qualifies as “deep tech”—it’s a very specialized field, and we needed somebody who not only knew the business side of things, but also understood quantum physics and quantum information science. On top of that, global experience is a must for any successful CEO of a startup in our field. Happily, we had plenty of interest from venture-capital firms, but finding our CEO was the final piece that took a while to fall into place.

Furuta: Yes, I’ve heard from other people that the shortage of management talent is one of the factors preventing the growth of R&D startups in Japan. But it sounds like you were able to find someone?

Aoki: In March 2022, Waseda University Ventures introduced us to Hirose Masashi, our current CEO, who was kind enough to say “Yes! Let’s do this!” And since then things have been proceeding at lightspeed. Hirose studied in the laboratory of Professor Itoh Kohei at Keio University, who studies semiconductor qubits, then got a PhD from MIT and had a consulting career at McKinsey & Company before we were fortunate enough to have him join our team.

Furuta: So he’s an executive with a PhD in physics. In recent years we’ve seen more and more people with a strong science background playing key roles in high-tech startups in Japan as well as overseas.

Aoki: Absolutely. One thing I’d love to tell students and young researchers in Japan is that there’s a high demand for folks who pursue that sort of managerial career path after getting their PhD.

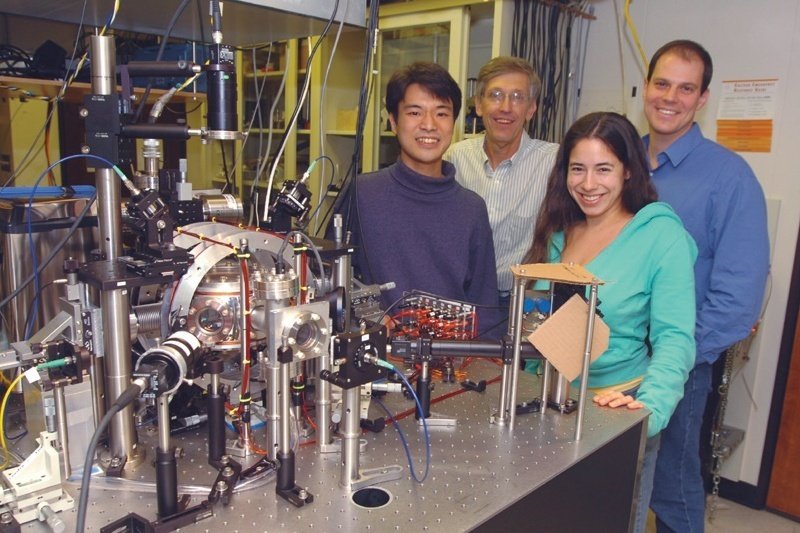

After Hirose agreed to join NanoQT, my former postdoc Goban Akihisa, who did research in my laboratory at Waseda, also signed on as CTO. He did his PhD with Professor Jeff Kimble at the California Institute of Technology, then did research on precision atomic measurements at the University of Colorado. Hirose was in the U.S. at the same time, and they had known each other’s names. The three of us—Hirose, Goban, and myself—first met to discuss in person at the beginning of April, and we decided right then and there to go for it: I was certain of course, but the other two apparently figured “You know, with this team of three it just might work.” And we launched the company just 3 weeks later.

Furuta: My background is in physics as well, and one thing I remember is that, in the past, people who came out of physics graduate school to take non-research jobs were greeted rather coldly by their professors. I guess things have changed a lot since then!

Aoki: I myself started out about as far as one can get from being venture-minded. The fact that I nonetheless eventually started thinking about starting my own company is something I attribute largely to my experience in the U.S. Before Goban was a PhD student in Jeff Kimble’s laboratory at Caltech, where many talented researchers gathered from all over the world, I worked in that laboratory myself, and the idea that we could be working on the same team, conducting experiments together and doing our research in adjacent rooms every day, was about the most exciting thing I could possibly imagine.

These days, all sorts of ideas are constantly bursting forth, whether we’re eating lunch together or discussing how to tune our experimental apparatus. There’s a certain sort of chemical reaction that takes place when smart people gather together and interact with each other—new brainstorms are constantly springing out of the woodwork. My dream is to make our startup into that sort of environment, where talented young Japanese researchers can devote their full attention to doing research.

Furuta: Would you say you’re achieving your goals?

Aoki: When NanoQT was just starting to get going in earnest, we were fortunate to have several of Japan’s best young researchers in this field, some incredibly smart people, agree to work with us. More recently, we’ve been getting inquiries from talented overseas researchers as well, and some of them have even agreed to join us too. I’d say things are going about as smoothly as I could have hoped.

Furuta: Well, here’s hoping that NanoQT becomes a model for how to launch an R&D startup in Japan. Professor Aoki, thank you very much for your time today.

Written by Furuta Aya

Photos by Mori Takahiro

Edited by: Sci-Tech Communications Inc.

Related information

■ Moonshot Research and Development Program

■ Moonshot Goal 6

Realization of a fault-tolerant universal quantum computer that

will revolutionize economy, industry, and security by 2050.

■ Goal 6 R&D Projects

Large-scale quantum hardware based on nanofiber cavity QED

(Project Manager: Aoki Takao)

■Nanofiber Quantum Technologies, Inc.